KHENIFRA, Morocco (AP) — For decades in the Moroccan town of Khenifra, Jacques Leveugle was simply known as the thin Frenchman who swept the streets at dawn, offered free language lessons and organized outings for schoolchildren.

He spoke fluent Arabic and Morocco's dialect, as well as Tachelhit, an indigenous language widely spoken by the region's ancient Berber people — skills that neighbors said helped him integrate into the community. He rode his bicycle to the local market, dressed simply in jeans and a button-down shirt, and opened a small library for children in the working-class Lassiri neighborhood.

Now the 79-year-old is behind bars and under formal investigation in France, accused of raping and sexually assaulting 89 boys over more than five decades across several countries, a case made public by prosecutors in France last week. They said Leveugle also acknowledged smothering his mother to death when she was in the terminal phase of cancer, and later killing his 92-year-old aunt.

Many of the sexual abuses occurred in North Africa, where Leveugle spent much of his life and built a reputation as a devoted teacher and a respectful man.

The crimes were discovered when a relative of Leveugle's found his digital memoir on a USB drive and turned it over to authorities.

Shock in Morocco and Algeria

In Morocco, where Leveugle lived until his arrest in 2024, he is suspected of abusing more than a dozen boys, Grenoble Prosecutor Etienne Manteaux told The Associated Press. In neighboring Algeria, where Leveugle worked as a foreign language teacher for eight years in the 1960s and 1970s, he is suspected of abusing at least two children.

The revelations have sent shock waves in both countries, and renewed attention to child exploitation in a region where activists say abuse remains persistent and underreported.

“This case is of exceptional seriousness and naturally provokes deep indignation,” Najat Anwar, president of Moroccan child protection association Don’t Touch my Child, told the AP. “We are prepared to join the case as a civil party … if Moroccan witnesses or victims come forward.”

The AP spoke with a dozen people who directly knew Leveugle, including his neighbors in Morocco and former students in Algeria, as well as Moroccan officials briefed on the case. Those who knew him described a man widely viewed as discreet, helpful, and who loved to spend time with kids.

On the narrow streets of Khenifra's Lassiri neighborhood, home to many conservative Moroccans, the crisp sweetness of a winter morning contrasts sharply with what residents describe as a sense of shame they feel since prosecutor's revealed Leveugle’s alleged crimes last week.

They feel insulted and humiliated. Many are now considering moving out. They all spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of harassment or retribution.

They pointed toward Leveugle’s house, an unfinished, unpainted, single-story building surrounded by fig trees, sitting alongside a river. Children play nearby.

Residents said ‘’Monsieur Jacques,'' as he was known, funded local projects and helped people find jobs, sometimes even giving out cash. Khenifra has long had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country, and many residents work in the informal sector. People often leave town in search of better prospects.

Residents described how Jacques once took children to a well-known regional lake, Agelmam Agezga, and told them to swim naked, starting by himself and claiming it was healthy. In Moroccan culture, and more broadly in Islamic tradition, men are not permitted to be naked in front of one another.

One neighbor said his ability to trust people is so shaken by the news that he refused to let his 5-year-old son sleep at his brother's house.

Leveugle was born in the 1940s in the French city of Annecy, and first arrived in Morocco in 1955, according to a Moroccan official with knowledge of the case. Leveugle's father worked at the French Embassy, and Leveugle attended school in the Moroccan capital during the final years of the French protectorate, the official said.

Leveugle later held Moroccan residency and had no known criminal complaints filed against him in the kingdom, according to a Moroccan justice official. Both officials were not authorized to be publicly named according to Moroccan government rules.

A teacher who never raised suspicion

Neighbors said Leveugle moved in the early 2000s to Khenifra, settling in the Lassiri neighborhood. Residents said he frequently spent time with teenage boys between 13 and 15.

He worked as a private tutor and, according to neighbors, offered free lessons, organized school outings and sometimes provided financial assistance to families. Some neighbors said he also bought houses and vehicles for local residents and helped people immigrate to Europe.

His frequent time with teenage boys occasionally prompted questions about his limited interaction with adults.

French investigators identified 89 victims of Leveugle, boys aged 13 to 17, after examining a 15-volume digital memoir found on a USB drive that one of his relatives turned over to police, the Grenoble prosecutor said. He said Leveugle’s victims in Morocco date back to at least 1974.

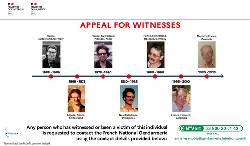

French authorities suspect there are more victims, and have issued an international appeal for witnesses. The prosecutor told The AP that French investigators are expected to travel to Morocco to gather evidence. Moroccan authorities have not made public comments.

The French prosecutor did not say whether an investigation had been opened in Algeria, where Leveugle taught at three schools. The revelations have left his former students reeling.

“I was stunned when I learned that,” Ali Bouchemla, who studied French under Leveugle in the late 1960s at a school in northern Algeria told the AP. He recalled a “devoted and very good teacher” who never raised suspicion.

Another former student, Lahlou Aliouate, similarly described a dedicated instructor with a professional demeanor.

Child protection advocates say Leveugle’s profile reflects patterns seen worldwide.

“Perpetrators often present themselves through educational or cultural activities, cultivate a respectable image and leverage social or cultural prestige to gain trust,” said Najat Anwar of Don’t Touch my Child. “They then target children in vulnerable emotional or social situations.”

...

Copyright © 1996 - 2026 CoreComm Internet Services, Inc. All Rights Reserved. | View our

Copyright © 1996 - 2026 CoreComm Internet Services, Inc. All Rights Reserved. | View our